Denoising

Charlie Moore and Jeff Blake

Abstract

For this project, we addressed the problem of audio files containing background noise. We worked with data containing clean speech files and also those same speech files with added background noise, and we created a neural network model to classify a wav file as noisy or not. Overall, our model was very successful, obtaining an evaluation rate on test data of 98.9%.

Github repository: denoising

Introduction

This project aims to address the first step in denoising audio signals: classifying the presence of noise. In particular, we aimed to classify added noise in speech signals. Denoising can be used in various ways, essential in providing cleaner signals in music production, restoring historical recordings Moliner and Välimäki (2022), or even studying our environment (as in the research on noise filtering for beehives from Várkonyi, Seixas, and Horváth (2023)). Previous attempts at audio classification and denoising use various methods of processing signals. A study by McLoughlin et al. (2020) used a combination of a spectrogram and a cochleogram (both 2D representations of an audio signal) alongside convolutional and fully connected layers for their model. Similarly, Verhaegh et al. (2004) tests the efficacy of different processing techniques, finding that running a signal through a sequence of filterbanks achieves the highest accuracy overall (90% across different classification tasks including noise). They also found the use of a mel-frequency cepstrum (MFCC) to be highly effective at 85% average accuracy.

Values Statement

We expect the users of our project to be engineers and/or musicians. This project is the groundwork for Denoising - removing the background noise from speech audio, resulting in clean, understandable audio. This is incredibly helpful not only for music, but any applications that convert speech to digital audio - for example: enhancing phone call quality, and speech-to-text accuracy, which many people will benefit from.

While we hope these applications will only improve the quality of life for people using these tools, we must understand a potential source of bias in the data: all the audio clips are spoken in English. If this is the only project/data used in denoising applications and is applied to technology used by those who speak other languages, it could potentially diminish the quality of their audio.

Our motivation for this project stems from our interest in electronic music. Vocals are particularly tricky to mix well (sound good within a track), and it makes a world of difference when the incoming audio file has been recorded at a high quality. Historically the way to accomplish this is with high-grade equipment, which can be very expensive. Using denoising software is a cost-effective alternative for clean vocal files for producing music.

The core question of this project is: would the world be a more equitable, just, joyful, peaceful, or sustainable place based on this technology? We believe that as long as more audio of all languages is incorporated, the answer is yes.

Materials and Methods

The Data

Our project is based on the data from the Microsoft Scalable Noisy Speech Dataset Reddy et al. (2019). This dataset obtained access to two speech datasets by license, one from the University of Edinburgh Veaux, Yamagishi, and King (2013) (where speakers across Great Britain were recruited by advertisement) and one from Graz University Pirker et al. (2011) (recruiting native English speakers through advertisements at various institutions). Similarly, MS-SNSD obtained noise samples by license from freesound.org (a website which allows for user submitted sound samples) and from the DEMAND dataset by Thiemann, Ito, and Vincent (2013). As such, these samples were created by researchers or freesound.org users recording their environments (traffic, public noising, appliances humming, etc.). The MS-SNSD provides a Python program to automatically combine the speech and noise data.

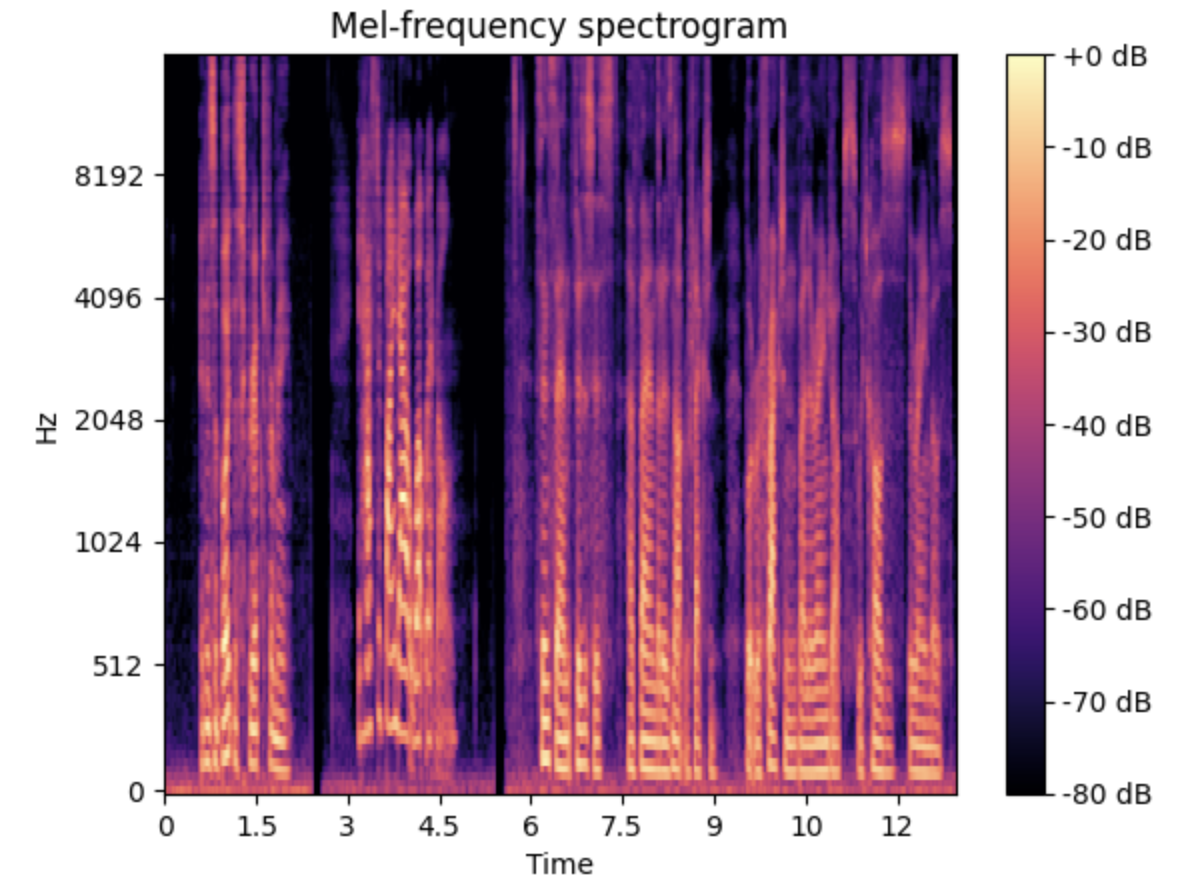

After reading in the data from a wav file, we converted it to a mels-spectrogram. Each row (or 2D array before flattening) of the data represents one audio file as a mels-spectrogram. These audio signals are 10 seconds of speech, either clean (no noise) or accompanied with added background noise. One limitation that exists with this dataset is that it does not contain recordings of languages other than English. As such, training a model on it does not guarantee its usefulness across languages.

Here is a sample image of a Mel Spectrogram:

Our Approach

In the processing of our data, we used the mels-spectrogram representation of 160000 sample audio files (cut off at exactly 10 seconds for consistent sizing). In converting these audio files to spectrograms, we had data instances of size 128 x 313 pixels, or 40064 features per instance of data. For our targets, we just created a vector that represented whether or not an audio sample had noise added (1 if noise is present, 0 if the signal is clean). We used a subset of our data (around ~3200 audio files) in order to limit training time. Our model was trained on Google Colab using the T4 GPU when available (and its default CPU when not); our model consisted of a convolutional layer, and linear layer. While we tried to add more complexity to our model, we immediately saw a dip in accuracy (and our accuracy results with the current model were already promising). We evaluated our model in terms of accuracy on a test set of 662.

Results

Our neural network model yielded 0.989 testing accuracy, after going through 10 training epochs and having 1.000 training accuracy. Compared to a linear model we implemented with only a linear layer that scored 0.941 testing accuracy, our neural network model with a convolution layer and non-linear layer is much better.

Conclusion

Our project classified audio files as containing background noise or not with a highly accurate rate on unseen test data, yielding a successful neural network model. The data from Microsoft made it easy to integrate with python’s audio packages, and allowed us to customize the noisy files to our specifications.

By converting 1-dimensional wav files into 2-dimensional Mel spectrograms, we were able to do image classification and use convolutional layers. This data is especially strong because it shows both amplitude and frequency over time, rather than just amplitude as a regular wav file does. The actual model pipeline was surprisingly simple, using only a 2d convolution layer, non-linear function, then flattening and a final linear layer to condense to the two possible outcomes.

In the future, the changes we would like to see most are A) adding other languages to the dataset. By including other languages in the dataset, our model trains on more diverse data and then is able to recognize not just English, but any human-spoken language. This will ensure that in future applications that use this model, all languages will be treated equally. If the data fails to include more diversity in the languages and the model is applied to all languages, it could work against people and diminish the audio quality rather than improve it. Additionally, if we had more time we could B) remove the background noise, yielding clean speech files. This is the ultimate goal that this model could yield.

The effectiveness of our model shows that denoising applications and cleaner digital audio are right around the corner.

Group Contribution Statement

Charlie

We split up the writing fairly evenly - on the proposal, I did the planned deliverables, ethics statement, and timeline, and Jeff did the abstract, motivation/question, resources required, and risk statement. On the blog post I did the abstract, values statement, results, and conclusion, and Jeff did the introduction, materials and methods. For initial visualization, Jeff created a Fourier Transform to plot frequency, and I made a soundwave plot of amplitude. We did some pair programming to vectorize the data, taking it from wav files to Mel spectrograms to tensors ready to be used as training data - but Jeff led the research and implementation of Mel spectrograms. I transferred code to Google Colab and devised a way to use command line tools to import our data and execute the noise file synthesization. Jeff set up a linear model and neural network pipeline, and I did lots of experimentation to increase our accuracy - ultimately ending up with an extremely simple pipeline. I also designed the presentation slideshow.

Jeff

Focused more on the data processing portion of the source code. This included the processing of the data into mels-spectrograms and the creation of tensors for the data. In doing so, they also visualized the test mels spectrogram value. They also led in the writing of the introduction and the materials and methods sections of the blog post. Further, they fixed bugs that were causing roadblocks in the training process, like making sure that the data was of the correct dimensionality (e.g. adding in an extra dimension for the one color channel the data has).

Personal Reflection

This was a very successful project. Not only did we achieve a high classification rate on our model but I learned a lot about digital audio and Google Colab, further solidified my knowledge on data vectorization, torch, and neural networks, and had fun doing it!

I feel great about what we achieved - for the group, we met our initial goal big time. Individually, I exceeded all the goals I set in relation to the project at the beginning of the semester. These were mostly in regards to the presentation of the project - writing the proposal, blog post, and presentation. We and Jeff had great communication - splitting up work evenly when it was convenient, meeting together at key points in the process, and doing some partner programming.

It was great to have some unique data to work with that we hadn’t tackled in class. I learned about Mel spectrograms and we made the decision to classify those as images rather than wav files, which I think is really cool. I also learned a lot about Google Colab - a resource I’ve never used before. I learned about GPUs (even buying some GPU tokens when we were down to the wire with time) and importing data into Colab. It was a fun process to play around with the neural net pipeline, although I’m disappointed that I wasn’t able to significantly improve it with more layers, I just had to mess with the parameters of a simple layer and nonlinear function.

I am very excited to continue working with audio in the future. I’m very interested in digital audio, and I’m happy that I’ve added a machine learning layer (haha) to my knowledge of this area.